Messing with LLM's for Fun and Profit

I'm very much a "local everything" kind of guy, but currently hardware to run massive 1.7 trillion parameter LLM's isn't something I can really justify, so compromises need to be made.

Introduction

I've been trying to build my institution around Large Language Models (LLM's) - getting a feel how to use this tool. So I've been messing with LLM's a year or two now, ultimately seeing if I can introduce them into my existing developer workflows. While I haven't been impressed by any kind of "expert knowledge" inferences, I do see the potential of using LLM's to augment human expertise - although, I think we are rather far from LLM's being used to make any unsupervised decisions.

In my experience, LLM's are really good at:

- Rewriting/summarizing/expanding input (be it text, images, sounds, etc.). This includes synthesizing unique text from a small input as well as summarizing large inputs into smaller outputs.

- Aiding in locating information e.g. Discovery of new (to me) information.

And LLM's are really bad at:

- Generating something completely novel e.g. something that doesn't exist directly, or indirectly in training input.

- Handling nuances - after all, LLM's are just probability engines. I suspect that better training/more data would help clean this up.

- Anything that requires exact and cited quotes - since this information is mostly lost when building the LLM. I think this shortcoming can't be resolved by larger models, we'll need a multi-system approach (a RAG), a whole-framework supporting the LLM.

- Any expert knowledge that is baked into the LLM - again, a probability engine that doesn't "understand" the nuances of colloquial language. I also suspect that better training data could help with this.

- Any structured data. Of course, better training aids here, as does basing predictions on a grammar (which some models support).

- Anything that requires mixing long-term memory elegantly with short-term memory.

Primer on Machine Learning

When creating typical software, a developer writes code. This code is an "algorithm", or a set of mathematical steps for the computer to execute (remember NP-complete from CS theory?). Some problems are so complex, that humans can't possibly design the "algorithm" to effectively model the system. To work around this, we effectively brute-force the problem - creating approximate, imperfect, and almost organic solutions. Doing this systematically is basically the field of machine learning, when the "machine" builds an "algorithm" so that an input is transformed into some reasonable output.

While there are many techniques and approaches, the most common is the so called "neural network". Roughly, the neural network attempts to model how we believe neurons in the brain operate. A text-book neural network might look like this:

Each neuron is simplistic, typically accepting some input signal (e.g. a number) and passes the signal after some transformation onto the next layer, through connections to other neurons. Training involves adjusting these neurons and their connections (weights) to "shape" the network so that given input produces "good enough" output. This is typically done automatically using different techniques e.g. supervised learning, unsupervised learning, etc.

Neurons don't contain intelligence or real memory, but when many work in cooperation, the presence of something intelligent can be formed. Similar to how each cell in the human body has no intelligence, but when 40+ trillion cells operate in corporation, we get Shakespeare (also Velma (2023), but we'll ignore that).

Introducing LLM's

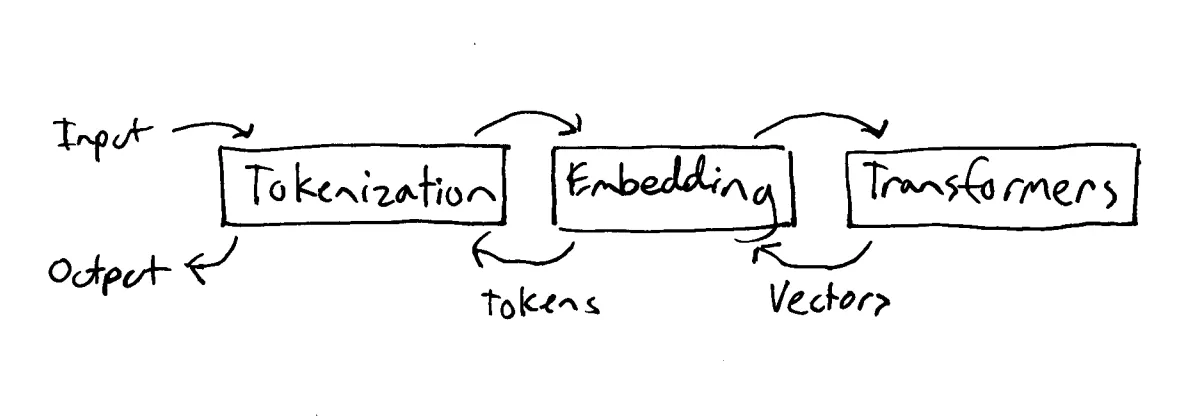

Large Language Models (LLM's) are artificial neural networks using a transformer architecture. Abstractly, there are three components that we care about:

- Tokenization - converting combinations of characters into numbers.

- Embedding - mapping tokens into a multi-dimensional space based on relationships between tokens, producing a token vector/matrix.

- Transformation - transforming incoming vectors though many transformation layers to produce probable output vectors (which get converted back into text).

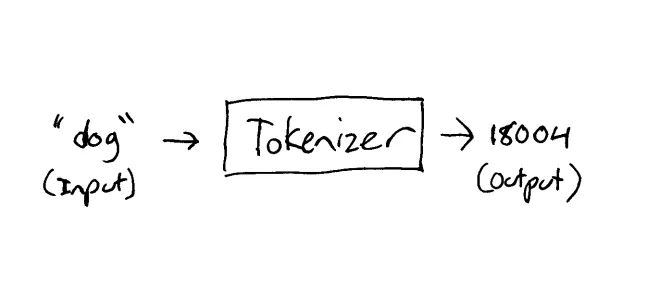

Tokenization

As mentioned before, we need to convert unstructured text into something a machine can understand, this is typically converting the text into a stream of numbers using a tokenizer.

Naively, we could convert each character into their UTF-8 number:

Input:

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog

Becomes:

["T", "h", "e", " ", "q", "u", "i", "c", "k", " ", "b", "r", "o", "w", "n", " ", "f", "o", "x", " ", "j", "u", "m", "p", "s", " ", "o", "v", "e", "r", " ", "t", "h", "e", " ", "l", "a", "z", "y", " ", "d", "o", "g"]

Or:

["84", "104", "101", "32", "113", "117", "105", "99", "107", "32", "98", "114", "111", "119", "110", "32", "102", "111", "120", "32", "106", "117", "109", "112", "115", "32", "111", "118", "101", "114", "32", "116", "104", "101", "32", "108", "97", "122", "121", "32", "100", "111", "103"]While this does fulfill the goal of making the text machine-readable, we end-up losing context and is rather inefficient (remember Huffman trees from CS?). For example, fox has far more semantic meaning then ["f", "o", "x"], so modern tokenizers are typically aware of basic text constructs e.g. whitespace separates words.

For example, using the LLaMA tokenizer, would produce the following:

Input:

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog

Becomes:

["", "The", " quick", " brown", " fox", " jumps", " over", " the", " lazy", " dog"]

Or:

["128000","791","4062","14198","39935","35308","927","279","16053","5679"]Some LLM's have additional context tokens, in the above example, token 128000 has a semantic meaning of "beginning of the sentence".

Now, we can't possibly assign a token to every possible word, instead tokenizers attempt to break down words it doesn't know about into "something" (aka, sub-words), this is important for things like acronyms or proper names. For example:

OWCA - The Organization Without a Cool Acronym

128000 - ''

3387 - 'OW'

5158 - 'CA'

482 - ' -'

578 - ' The'

21021 - ' Organization'

17586 - ' Without'

264 - ' a'

24882 - ' Cool'

6515 - ' Ac'

47980 - 'ronym'Note that OWCA is not a common acronym, so the tokenizer produce two tokens OW and CA. But for example, NASA is assigned its own token:

NASA - National Aeronautics and Space Administration

128000 - ''

62066 - 'NASA'

482 - ' -'

5165 - ' National'

362 - ' A'

20110 - 'eron'

2784 - 'aut'

1233 - 'ics'

323 - ' and'

11746 - ' Space'

17128 - ' Administration'What's interesting is Aeronautics has no single token, so the tokenizer breaks the word into multiple parts A, eron, aut, ics. Case also can matter, since case does provide semantic meaning. So going back to the OWCA example:

an Acronym

128000 - ''

276 - 'an'

6515 - ' Ac'

47980 - 'ronym'

an acronym

128000 - ''

276 - 'an'

75614 - ' acronym'Simply changing the case of a word, changes the produced token, which might change the output of the LLM. Misspelled words also produce completely different tokens.

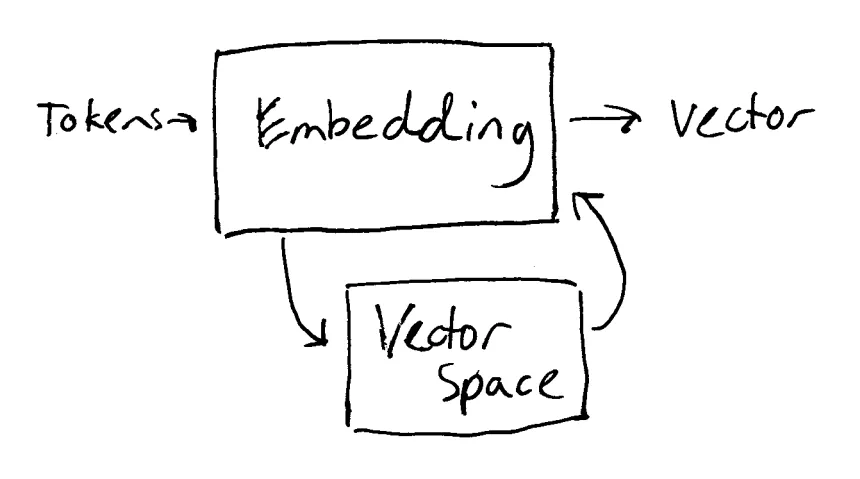

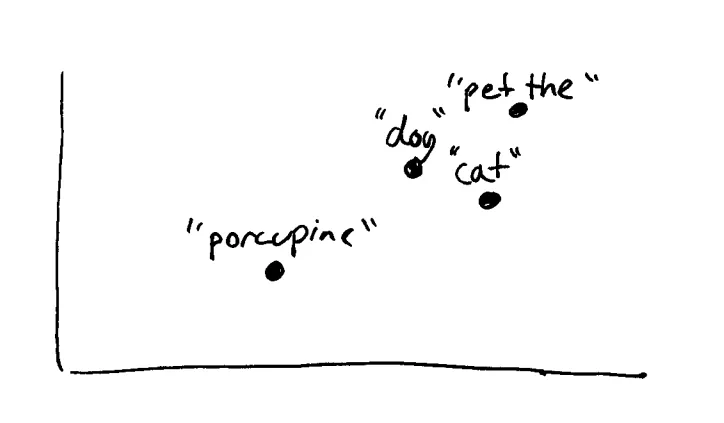

Embeddings

The next step is to map the tokens to their semantic meaning. This is called embedding or vectorization, and can be quite difficult. Many tokens have multiple meanings and tokens can change the meaning of other tokens. The current solution to this problem is mapping tokens into a multi-dimensional space, where concepts are place spatially near similar concepts, with the aid of an embedding model.

Each dimension in the embedding model can represent a different concept, like color, sounds, Latin root, etc. Dimensions don't have to be human readable or even well defined.

While the embedding model can be simple lookup table, the embedding model can also be another neural network, trained to produce an

organically generated algorithm. In all likelihood this network will construct completely novel relationships, that might make no sense to humans. I like to think of this as an analog to our "gut feeling" or "intuition". This fuzziness allows LLM's to generate text based on an input emotion, even though the LLM may fail at basic math.

Transformation

Using LLM's

Types of LLM's

What really confused me for a while was the difference between text-completion and instruct based LLM's. I think this mostly is due to Chat-GPT being the first LLM I messed with.

Optimizations

Quantization

Padding

Designing Prompts

On Copyright Training Data of LLM's

I'm going to focus on the more controversial aspect of LLM's, or rather, how they are created.