BTRFS: Lessons Learned through Blood and Tears

Short Introduction

I don't try to hide that I love BTRFS. Over the past 10 years, I've stored hundreds of TiB of data on BTRFS, and BTRFS has been with me through disk corruption, disk failures, etc. To put this in context, in the same time frame, I've lost multiple arrays due to mdadm bugs, I've lost EXT4 volumes due to crashes, and don't get me started on FAT (*shudders*).

I find BTRFS incredibly stable and I've yet to lose data. It's so stable, I'm starting to move all my systems completely onto BTRFS (from EXT4). It's not all roses and hard drives though, BTRFS is a semantically different from what we've used before - this is my write-up of the lessons I've learned caring for BTRFS.

What is BTRFS?

BTRFS is in a class that I call: third-generation filesystems. These generations aren't a "real" designation, but it's where my mind goes when categorizing the different filesystems over time.

I'm conceptually skipping over a lot of history. Imagine there's a generation 0 somewhere.

First, we had simple first-generation filesystems (compared to modern filesystems at least), like FAT or EXT2. These were great because they standardized disk formats and introduced filesystem staples, a step in the right direction. But there were shortcomings. The glaring was being the lack of atomic write operations (power loss could corrupt data without a great way to reverse back to before the write operation was lost). The filesystem couldn't guarantee consistency.

Then came what I call the second-generation filesystems, such as NTFS or EXT3/EXT4 - all journaling based filesystems. Journaling was great, since it allowed for atomic-modifications in relative safety (not prefect, but much better). The journal keeps track of modifications, and if something bad happens, the filesystem could use the journal to reconstruct a more consistent state before the error occurred (say, power loss), which is awesome! There's a reason why most SQL databases tend to use some kind of a journal, although, typically much more complex (e.g. a binary log).

Now we are in what I call the third-generation, copy-on-write (COW) and bit-rot aware filesystems. Modern filesystems like ReFS (to replace NTFS on Windows), BTRFS, ZFS, etc. are all in this camp.

You might noticed that COW and bit-rot detection tend to go hand-in-hand in a lot of implementations. It turns out storing hashes of data blocks gets really difficult if modifications to the blocks are allowed later (you don't want to re-calculate the hash of an entire file, if you just append to the end, right?). The natural solution is to adopt a small amount of immutability.

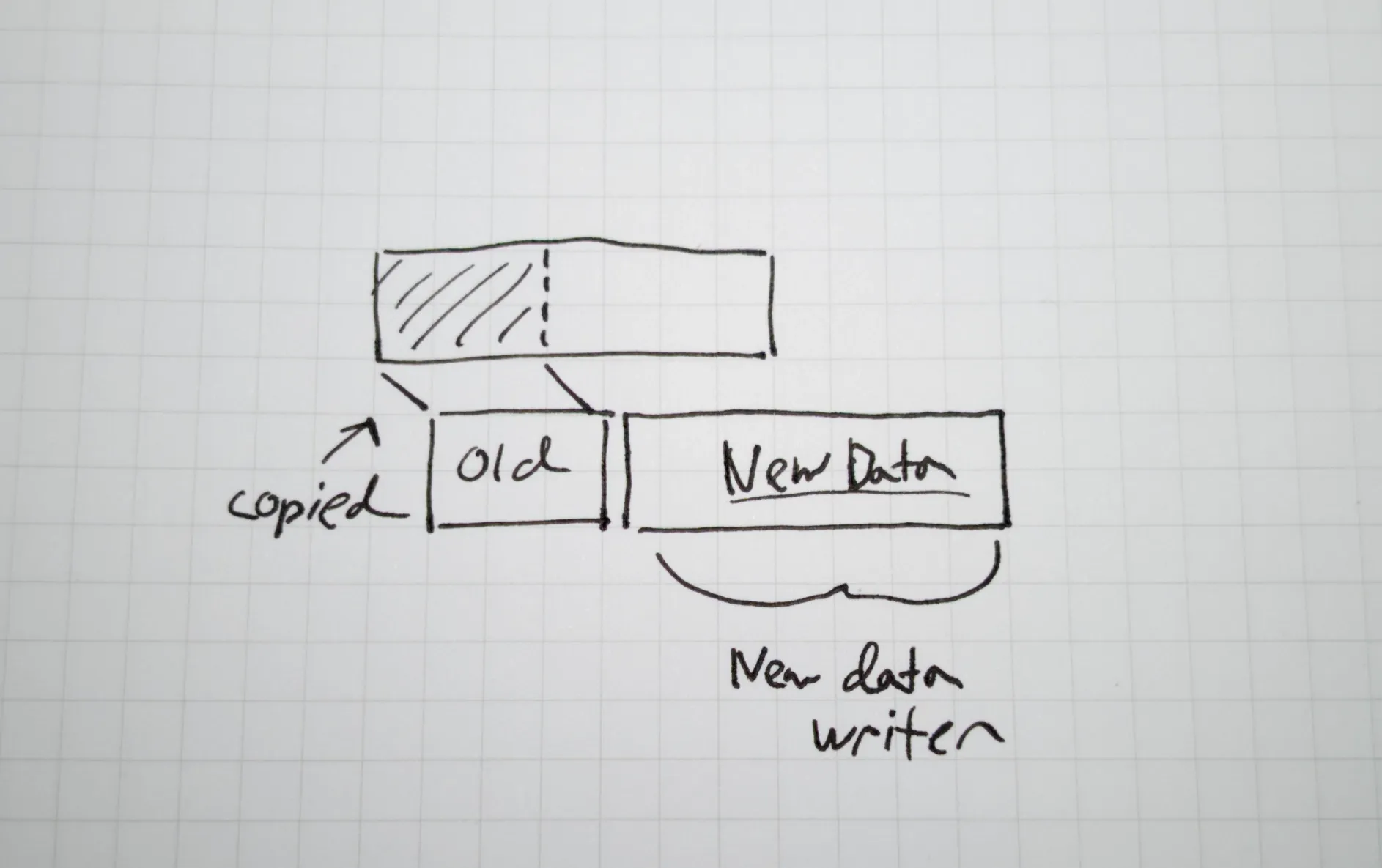

And this is what COW does. Both the old state of a file being modified, and the new state, exist on the disk at the same time (hence, copy [the data before] the write). After the commit, then the old data can be removed (or in many cases, simply marked as removed). This guarantees data safety on a crash (assuming the disk isn't faking the status of write operations, some do). In many COW systems, there is no need for a journal (although, it can still be useful, e.g. replication).

Industry wide, there are endless examples of systems adopting COW semantics. Docker/OSI containers made heavy use of COW to reduce resource needs of many containers sharing the same image. PostgreSQL internally uses COW semantics, significantly reducing the complexity of transaction rollback (don't you love nearly instantaneous rollback? Looking at you, only-semi-ACID-compliant-MySQL...).

And there's a reason, COW naturally makes a lot of cool features possible. For example:

- As I mentioned, bit-rot detection and general data crash safety.

- Offline file deduplication - multiple files can safely point to the same logical chuck of data (like a hard link, without hard link aliasing).

- Instantaneous and fully consistent snapshots or file cloning.

- Better support for zoned storage (those annoying SMR disks).

- And many more!

But not everything is perfect, like many things, COW has problems. In software engineering, we tend to like making data structures immutable. We like this because of the safety it provides, but it also can make problems regarding performance. BTRFS naturally has the same theoretical problems, as well as completely new problems that filesystems traditionally didn't have before it.

6 Lessons Learned

So here are the lessons!

BTRFS Is Flexible

Lesson #1: It's okay to change your mind later.

Nearly every feature in BTRFS can be migrated to, Meaning you can start off with a single drive, and then use RAID1 or RAID0 later. You can disable or enable quotas at any time, or modify COW semantics anywhere. Even stuff like compression algorithms can be changed.

And all of this online!

I can't stress how awesome this is. The last I tried to change the layout of an mdadm array, I had to restore a 40TiB server from backups (read, I don't trust mdadm). For BTRFS, I can switch between RAID1 and RAID10 completely online, and I trust BTRFS to not eat my data.

BTRFS's Failure Mode

Lesson #2: BTRFS might care more about data safety, than you do.

When BTRFS fails, BTRFS tends to fail-safe by entering a read-only mode. At face value, this seems awesome, failing in a data-consistent way, a hallmark of a good system. It can be annoying though. For example, if a BTRFS array, in RAID1 mode, becomes degraded (say a hard drive stops responding), you have one-shot at fixing it. The old BTRFS wiki says this:

Even if there are no single profile chunks, raid1 volumes if they become degraded may only be mounted read-write once with the options

-o degraded,rw. Source

Due to this, a server failure involved me copying the read-only data over to a new BTRFS volume, as I accidentally rebooted twice. Annoying is a understatement, especially when you don't have the hard drive spares... Sometimes you just want things to work, regardless of data durability.

Thankfully, I haven't ran into this in a while.

Care for BTRFS Responsibly

Lesson #3: You need to care and nurture BTRFS. Preventive maintenance is recommended if your data is critical.

In some systems, say Ceph, the system takes care of you, by actively performing maintenance functions, like monitoring for bit-rot or rebalancing. BTRFS doesn't do much proactively, which can be a good thing or a bad thing. BTRFS tends to wear a lot of hats, you might see it used for interactive workstation usage, embedded IOT devices, or enterprise mass-storage - all with different needs. This bare-bones approach means, BTRFS can run on basically any system, but it also relies on you to care for it's needs.

That said, BTRFS has sane defaults that work in 98% of environments. BTRFS self-heals if it encounters corrupt data (assuming there's another copy), can automatically detect SSD's for SSD optimizations, and normally doesn't need to be rebalanced.

If your data is important, it is your responsibility to setup recurring scrubs at the time interval that is best for you, using the btrfs scrub command. So either a crontab or a Systemd timer. Scrubs will both detect issues, as well as automatically fix them (if possible).

I use this as systemd unit:

# /etc/systemd/system/btrfs-scrub@.service

[Unit]

Description=Scrub BTRFS filesystem (%i)

Documentation=man:btrfs-scrub

[Service]

EnvironmentFile=/etc/btrfs/scrub/%i.env

ExecStart=/bin/btrfs scrub start -B $MOUNT_POINT

IOSchedulingClass=idle

CPUSchedulingPolicy=idle

Nice=15# /etc/systemd/system/btrfs-scrub@.timer

[Unit]

Description=Trigger BTRFS scrub on filesystem (%i)

[Timer]

OnCalendar=monthly

Persistent=true

[Install]

WantedBy=timers.target# /etc/btrfs/scrub/-.env

MOUNT_POINT=/Note that IO scheduling class only works if your IO schedular supports it - the normally default

mq-deadlineschedular does not support IO priorities, but something likebfqdoes.

On that same subject, there is no active notification when BTRFS finds an issue. You are responsible for setting up monitoring. You can use btrfs device stats to get this information, I recommend the -c flag to return an exit code based on the results.

The output looks something like this:

btrfs device stats /[/dev/mapper/sda3_crypt].write_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sda3_crypt].read_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sda3_crypt].flush_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sda3_crypt].corruption_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sda3_crypt].generation_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdb3_crypt].write_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdb3_crypt].read_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdb3_crypt].flush_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdb3_crypt].corruption_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdb3_crypt].generation_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdc3_crypt].write_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdc3_crypt].read_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdc3_crypt].flush_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdc3_crypt].corruption_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdc3_crypt].generation_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdd3_crypt].write_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdd3_crypt].read_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdd3_crypt].flush_io_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdd3_crypt].corruption_errs 0

[/dev/mapper/sdd3_crypt].generation_errs 0

If any of these values are non-zero, you likely have a hardware problem. As always, monitor SMART if possible.

Morgan, from Doing Stuff, mentioned kdave/btrfsmaintenance, to get new BTRFS users started with a good reference of what scripts you can have in your maintenance toolbox.

COW Exacerbates Fragmentation

Lesson #4: You might need to monitor or actively prevent fragmentation, depending on your workload.

I think the most commonly known issue with BTRFS is the dreaded fragmentation problem. This is completely related to the COW semantics, so not just a problem with BTRFS (see ZFS fragmentation). To my knowledge, only ReFS seems to avoid this issue, but no one really seems to know how, given the closed source nature of the filesystem.

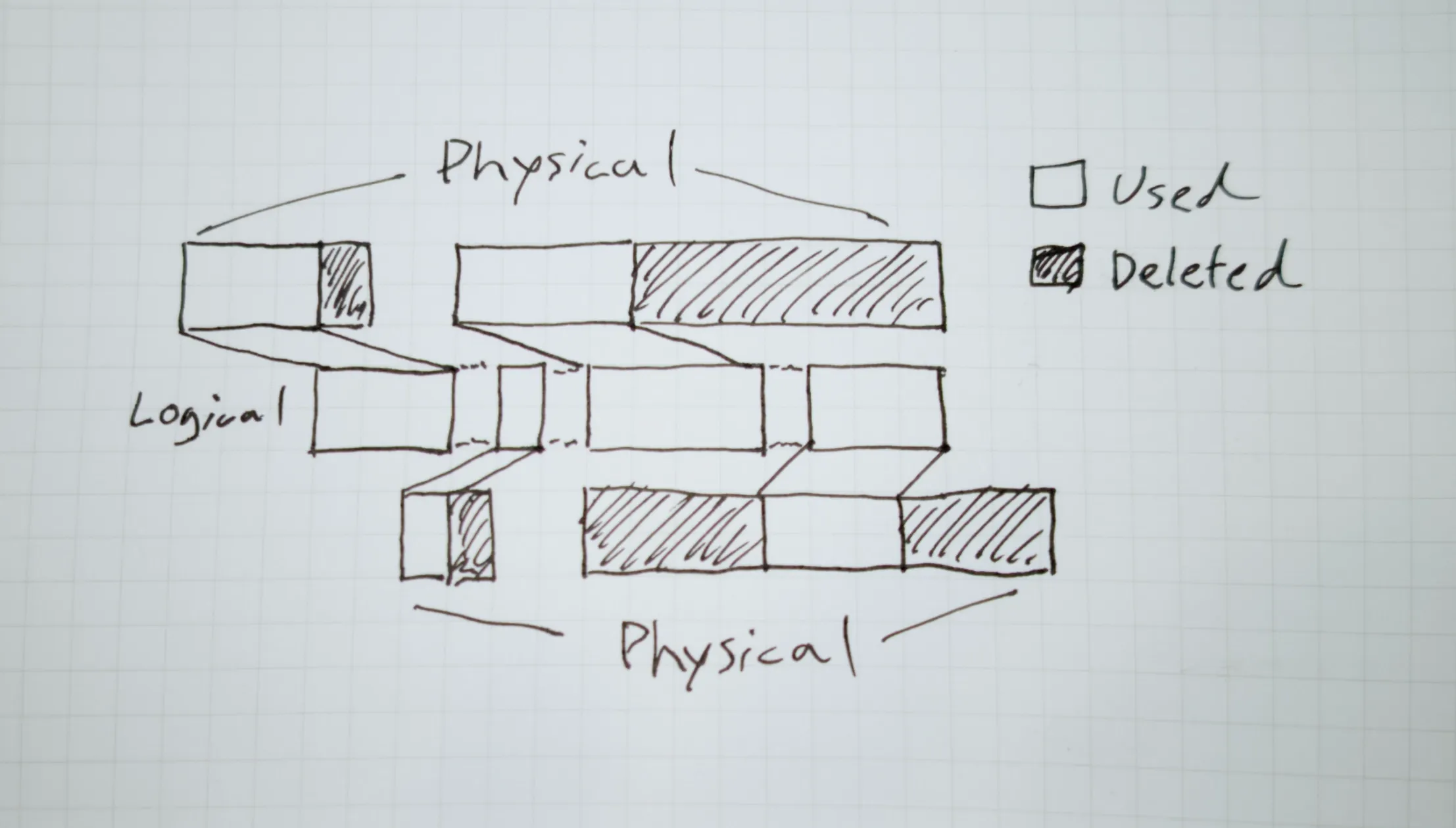

Ultimately many modifications to the same large file can cause significant data fragmentation where parts of the same file might be spewed across the physical disk. Not only is this bad for seeking operations (assuming spinning rust), but it can also increase storage waste, due to the metadata overhead and reduced data density.

This is largely not an issue for the vast majority of use-cases, and might never actually become a problem. You can kind of estimate how bad fragmentation is if you use something like filefrag

filefrag /bin/htop/bin/htop: 3 extents found

I just wouldn't use the output for anything other than a barometer. If this number is in the 1000's, you likely have a problem, but possibly not a problem that needs to be fixed.

If you need to solve fragmentation I think there's basically two schools of thought:

First, you don't let fragmentation happen by disabling COW completely. This works great for things like VM disks, where it's a good idea to tell BTRFS it's allowed to do in-place modifications (helps performance, prevents fragmentation, but decreases data durability on a crash).

# Note that this doesn't remove existing fragmenation.

chattr +C # <the file or directory you want to stop COW on>Or you let fragmentation happen, and defragment on an interval (or manually, as needed). This is perfect for those backups that eventually become read-only.

btrfs filesystem defragment -r # <the file or directory to defrag>But again, you likely don't need to defragment.

BTRFS Sizes Differently

Lesson #5: DF only shows part of a truth.

It's really common for Linux users to just run something like df -h on the command line to get an idea on free disk space. That only works maybe 95% of the time for BTRFS, as df only tells part of the story.

In traditional filesystems, disk use was measured by the number of bytes on the disk (ignoring sparse volumes, hard links, junctions, and other shenanigans). With COW systems, there is no longer a direct correlation between between the size of all your files, and actual disk usage. You can have 100TiB of files, all reflink'ed together, and only take up 2GiB of actual storage space. And since BTRFS supports compression, you can fit even more bytes onto your disk. I once compressed a 80GiB SQL Server database (running on Linux) using BTRFS compression down to 5GiB (way better than what SQL Server's native page compression was estimating it could do).

Another example, I once had a routine defragmentation eat over 800GiB of the available capacity on execution. This was unexpected, but thankfully, the defragmentation was canceled when that volume reached it's accounting quota (that was also unexpected, but a pleasant surprise. Seeeee, BTRFS cares). This wasn't due to reflinks being unmerged, but because recent deletions caused unbalanced disks - which caused BTRFS to artificially lower the available capacity to maintain data safety (I might be wrong here, I didn't spend a huge amount of time debugging this one). Running a balance returned free disk-space to what I expected.

So ultimately, a lot of variables go into how much capacity exists and is ultimately used. When in doubt, it's best to ask BTRFS directly:

btrfs filesystem usage /Overall:

Device size: 31.98GiB

Device allocated: 15.02GiB

Device unallocated: 16.96GiB

Device missing: 0.00B

Used: 8.28GiB

Free (estimated): 22.03GiB (min: 13.55GiB)

Free (statfs, df): 22.03GiB

Data ratio: 1.00

Metadata ratio: 2.00

Global reserve: 17.98MiB (used: 0.00B)

Multiple profiles: no

Data,single: Size:13.01GiB, Used:7.94GiB (61.05%)

/dev/mapper/nvme0n1p3_crypt 13.01GiB

Metadata,DUP: Size:1.00GiB, Used:171.58MiB (16.76%)

/dev/mapper/nvme0n1p3_crypt 2.00GiB

System,DUP: Size:8.00MiB, Used:16.00KiB (0.20%)

/dev/mapper/nvme0n1p3_crypt 16.00MiB

Unallocated:

/dev/mapper/nvme0n1p3_crypt 16.96GiB

It's not Complete, But That's Okay

Lesson #6: BTRFS is not feature complete, but it keeps on getting better.

What originally drew me to BTRFS was that it was in-tree, which is a blessing and a curse. On one side, you have rock solid stability and a migration path. On the other hand, BTRFS may not be as nimble as other filesystems who work out-of-tree.

In-tree and out-of-tree is referring to if the code is in Linus Torvalds's repo at-the-end-of-the-figurative-day. There is a out-of-tree BTRFS repo if you want the latest, but I think most of us use the version supplied by the kernel.

The go to example for this "development slowness" is BTRFS RAID5/6 stability. Currently it's rated as "mostly OK" (read, don't store important stuff on it yet), but historically, RAID5/6 had fundamental issues that made storing anything with RAID5/6 dangerous. Will RAID5/6 support ever be fully fixed? I don't know, although there are desires from BTRFS developers on a rewrite. It might say more that even with the issues with RAID5/6, BTRFS hasn't just nixed the code.

Even though BTRFS development hasn't been quick, BTRFS continues to make steady progress on new features, while retaining, in my experience, nearly perfect stability . The developers are completely honest on what is stable and what is not and the on-disk layout appears to have stabilized. All of these things are incredibly healthy for a new generation filesystem - where data durability and trust is king.

Not only is BTRFS improving over time, but application support is also getting better. It's not uncommon these days for applications to directly support COW filesystem semantics directly. The .NET runtime can detect that file copying can be done using reflinks, which avoid the copy from taking disk space until the copy is modified. .NET isn't alone here, many other open source projects have custom handling for COW too.

What I found really cool was that Docker/ContainerD have native support for BTRFS (similar to the traditional overlay2 approach):

btrfs subvolume list /ID 267 gen 1745178 top level 5 path var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes/e1408a5d2caf0fc69d4d470041906468de3cafdffe7bab49bec31e82325ad7a1

ID 268 gen 1745178 top level 5 path var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes/547ddbb037cb7d963d497223db6b6827b5cc34134d521ae018b8e2fce2672553

ID 269 gen 1745520 top level 5 path var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes/abbc656e07f9592873a944faa557c7a5af415e6b082a0d36d511c69a1b2761f8

ID 270 gen 1745520 top level 5 path var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes/b9355aa3005470bae7df10e460d0f6bf262b6f5879d641b74cd4959c4a3a5729

ID 271 gen 1745520 top level 5 path var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes/294d8221f65141ce2d18a3af44abdeac9732f7b252696e69ee3eb65d597c79e1

ID 272 gen 1745520 top level 5 path var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes/45f083f43514b3ffb62870cd39fff6ce8acadbbdac31d830f717d729ad8a24ab

ID 273 gen 1745520 top level 5 path var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes/b851a8b421655a7d5600375e1a8d3e2060f5b9443dbb412e94a851d36bab9339

ID 274 gen 1745520 top level 5 path var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes/2519d0c093a63974faee413d071390c5673d5db63e926aa905f83309bd9e2b8d-init

ID 275 gen 1745520 top level 5 path var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes/2519d0c093a63974faee413d071390c5673d5db63e926aa905f83309bd9e2b8d

ID 300 gen 1745430 top level 5 path var/lib/docker/btrfs/subvolumes/f0c64d63b2417784332903129ff900176b506a01c79c81522a16d59a32c9cfec

Summary

BTRFS is a member of the next generation of COW filesystems, and is likely to replace XFS and EXT4 as the default. So far, we've seen "official" adoption from the likes of OpenSUSE, Fedora, Mint, and Ubuntu. I also see industry trends valuing immutable distributions (Flatcar Linux) and distributions that support atomic upgrades (e.g. NixOS) benefiting greatly from the features that BTRFS provides.

BTRFS is also incredibly flexible and can run in places that heavier filesystems, like ZFS, just can't. Today, BTRFS looks like a good choice for workstation usage and archival storage. I think tomorrow is bright for BTRFS as adoption improves.

If you haven't messed with BTRFS, now's a good time to start!